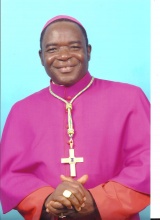

Matthew Hassan Kukah, Catholic Bishop, Sokoto, Nigeria

(Draft Paper Presented at the 2018 OMNES GENTES COLLOQUIUM at the Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium, November 12-14th, 2018)

This paper will address the issues anticipated in the presentation against the backdrop of the larger questions of political economy of development in Africa. My intention is to interrogate some of the assumptions we have about the African condition as a basis for understanding why those of us engaged in Dialogue must go beyond the surface. To this extent, I intend to make reference to the historical nature of the processes that create the conditions for our crises. Throughout the paper I will make some particular references to our Nigerian context.

To do this, I will divide the paper into four parts. First, I will provide a brief context of the African condition so as to help us understand how the past affects the present. Second, I will look the challenges of dialogue today within this context. Third, I will briefly look at the resources available to the Church as a leader in the course of Dialogue and the fulfillment of her prophetic mission. Lastly, I will conclude with some concrete suggestions for the way forward.

1: How did we get Here? A Context for our Condition:

On the surface, the themes here look very simple and straightforward. The first temptation is to think that we can simply address this topic by defining the key concepts such as Religion, Violence, Peace building, Integration and development. However, each and every one of these words is loaded with deep meaning, meaning for which context has to be provided. When we speak about the conditions of Africa, westerners are often impatient, using lenses drawn from their own experiences and history with institutions and systems, to judge or measure our performance. I believe that without an understanding of the African context, even we Africansassume that something is wrong with us. Thus, we often hear the questions such as; why does violence persist, whyare our institutions not working, why does corruption persist, what are the religious leaders doing? etc. Without attempting to make excuses, I believe that an understanding of contexthelps both Africans and their friends to think more clearly.

For example, if we speak of Religion today, which religionand which aspect of that religion do we mean? Different religious traditions elicit diverse meanings and interpretations among their adherents. Whether it is Christianity, Islam, Traditional Religions, Confucianism, Shintoism, etc, various strands exist in each community. Even within homogenous societies, some conflictinginterpretations and viewspersist as to the meaning of Life and Death, Development, Human progress or Peace in their societies.

When we speak of Violence, again, both perpetrators and victims view it from different and contrasting lenses, with each claiming convictions about the righteousness of their cause. We tend to externalize violence based on its physical expression as in wars and internal conflicts within societies. We tend to ignore the deeper structural conditionsthat make violence often inevitable. Even after the violence, there is often no common agreement as to causative factors, narration or interpretation of events.

For example, in Africa and most parts of the developing world, western colonialism was presented as a civilizing mission, one aimed at lighting up the Dark Continent. In doing this, the missionary enterprise was conflated with the colonial project. However, although both the colonial masters and the missionaries believed in the urgency of Education as a stepping-stone to modernity and development, there were deeper ideological differences. Thus, for example, whereas the missionary project on education was meant to benefit and liberate all, quite often, as in Northern Nigeria, colonial education focused on the children of the privileged as a means of perpetuating the existing order. Its focus was the maintenance of the old order, marked by the divine right of kings over their serfs. The notion and urgency of ending our civil wars and slavery presented colonialism as what Rudyard Kipling saw as, thewhite man’s burden[1].

With education, Africans began to see their condition, their loss of rights and dignity, the exploitation and appropriation of their lands and resources,as part of both the entire colonial and missionary projects. The first generation of educated Africans began to question the meaning of the presence of the white person, whether as missionary or colonialist, leading to the famous quip attributed to the late Jomo Kenyatta to the effect that:Before the white man came, we had our land but not the Bible. The white man came and taught us to how to pray with eyes closed. We learnt how to pray, opened our eyes only to discover that our land was gone! The struggle for independence began as a means of seeking the restoration of human dignity and control of resources.

Africans saw independence as the door that would lead their people to freedom, development and progress. However, by the time independence came, the trauma of colonialism had already taken its toll on local identities and worldviews. New ideologies posed conflicting challenges for an elite totally unprepared to govern in the new ways of the departing masters. Colonialism had seemingly offered Africa a cure worse than the disease. Colonialism had left the new African states and communities a legacy of severely fractured, divided and wounded societies, arbitrarily dismembered into new spheres that were coterminous with the boundaries of the influence of their foreigner invaders[2]. The details of these decisions do not belong here, but, when we add the destructive impact of years of slavery, we can understand the context of the African situation.

Today, years after independence, the legacies of bitterness arising from the historical experiences of post-colonial violence still lingerin the minds of our people. Independence and the new structures of power were marked by state sovereignty, new bureaucracies, standing national Armies, arbitrary borders, flags and national anthems. This is what a British scholar, Basil Davidson, would later refer to as the curse of the nation state in Africa[3].

The new African elite was saddled with administrative structures that had emerged from the rubble of their own systems whose destruction laid the foundation for colonialism. The result was that most African countries spent the first ten years of their independent lives fighting off military coups or struggling to cope with the domination by the bigger ethnic groups which had been placed over them. The continent is still dealing with genuine fears of domination based on the re-invention of colonial boundaries along Religion (e.g., Muslim vs. Christians in Nigeria), or Ethnicity, Nuer vs.Dinka (South Sudan), Kikuyu vs. Luo (Kenya), Hutu vs. Tutsi (Rwanda) etc.

As I have illustrated, whereas the states that emerged bore the marks of their colonial metropoles, similarly, the African Churches bore the same trademarks of their denominational metropoles. Thus, our communal landscape is littered with Churches depending on which denomination arrived where and when. As such,today, in the same cities or communities, denominational populations are clustered around particular areas. In some instances, in the southern states in Nigeria for example, deep cleavages have evolved between the Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, and Catholic Churches. Often, these differences are so deep that they become the basis for political loyalties.

In Northern Nigeria where Islam is predominant, these affiliations also manifest in the same way. For example, under the Brotherhoods, the Tijaniya are predominant in such areas as Bauchi, Kano and parts of the Middle Belt, while the Kadiriya are more predominant in the North Western parts of the North. Similarly, the more radical and non-Sufi groups such as the Izala or the Shiites are clustered around Katsina, Jos and parts of the Middle Belt. The members of Boko Haram are largely drawn from this mosaic of groups.

How feasible is Integrationin African societies given that today we have all been herded into structures of power that we can do little about? The terrain that makes integration so difficult naturally provides a backdrop for understanding the problems of development in Africa. Many will argue that both integration and unity have eluded Africa and this is why the continent continues to wrestle with these crises. Against the backdrop of massive frustration with Democracy and the inability of the African elite to deliver on good governance, the Church finds itself coming under severe pressure to resolve the issues of conflict and violence. Against this background of failed and failing politics, how should the Church address the problems of Dialogue and development? There are many challenges based on the fact that African history was never part of the Seminary clerical training and the result is that too many clerics at almost all levels have very limited understanding of the cultural, social and political history of their nations.

2: Dialogue & Mission: Challenges and Obstacles Today

I come from Nigeria. Our country is both famous and infamous. We are famous for very many things: a huge population of very good people, rated the world’s happiest and most religious people, we play very good football, we have had four Cardinals - one dead and three still alive, we have the largest Catholic population and the largest Conference of Bishops, we have the biggest oil reserves in Africa, and make tonnes and tonnes of money from oil. Yet, even among Nigerians, our country does not summon us to respect, thus preparing the ground for the stereotypes that have come to characterize us.

Today, the downside of my country’s story is that we are known as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, having lost over $500b in the last fifty or so years, we have just recently overtaken India as the world’s poverty capitals of the world, we have almost 15m children out of school with the north providing over 80%. Poverty levels, infant and maternal deaths are some of the highest in Africa. In almost every index, Nigeria like many other African countries has been stagnating. It is this frustration that has continued to fuel crisis and conflict in Nigeria in particular and Africa in general.

The story of corruption in Nigeria is a metaphor for interrogating the structures that have produced the inefficiency that drives negative development indices across the entire continent of Africa, bar one or two exceptions. Africa is corrupt, there is no doubt about that. However, the corruption in Africa is built on the foundations erected by the corrosive effect of colonialism and a capitalist ideology that has undermined the humanity of the continent.

The result is the massive hemorrhaging of resources that has rendered the continent largely comatose and merely a reservoir and backwater for the resources that the super powers require to drive their progress and development. The endless civil and cross border wars on the continent, the rise of violent militias, migration, the return of a culture of coups (Zimbabwe), are all manifestations of the crises of weak states, lacking in capacity to withstand the extreme ravages of western capitalism. As in the past, the western powers and their businesspeoplecontinue to wade through what a British writer referred to as a swamp full of dollars![4]

Since independence, Africa’s struggle for self-discovery and development has remained elusive. The political landscape has been littered with the carcasses of failed and successful coup plotters, leading to military and civilian dictatorships. In the late 90s, the end of apartheid and the return of Democracy along with the emergence of President Mandela, gave the continent and its people a ray of hope. The pair of President Olusegun Obasanjo and Thabo Mbeki proposed the ideals of a New Partnership for African Development, NEPAD, as part of the goals of an African renaissance. Under the NEPAD philosophy, African nations signed to the principles of what they called Peer Review Mechanism by which African governments would learn from one another by reviewing their development initiatives and performances.

Africans had hoped that these initiatives under NEPAD would fast track development on the continent especially after the then Secretary General, late Kofi Anan (1938-2018), the first African to occupy the position of the world’s top civil servant, pushed for what was known as the Millennium Development Goals. Set in 2000, the goals focused on:addressing extreme poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, and exclusion-while promoting gender equality, education, and environmental sustainability.Sadly, today, NEPAD and the goals of Peer Review have all fallen silent on the continent. Hardly any African country managed to meet the MDGs and for Africa as they all remained a dream deferred. Ostensibly, the United Nations has projected the realisation of another set of development goals by the year 2030, pledging that none will be left behind, but we know this is a tall dream.

The African Union, under pressure from within and without, decided to embark on another round of self-examination. Unable to explain the crippling inequalities, the curable and incurable diseases ravaging the continent amidst so much God given wealth, the African Union, in collaboration with the Economic Commission for Africa, summoned Dr. Thabo Mbeki, the former President of South Africa, to head what has come to be known as the Commission on Illegal Financial Flows. The initiative was meant toensure that Africa relies on its own resources, and reverse the tag it carries as the creditor to the rest of the world and the false claim that almost all countries had insufficient resources available for development[5].

The decision by the African Heads of the Governments of the African Unionto set up the Commission arose from the urgent need to address the problems of grinding poverty, mounting pauperization, instability and squalor in Africa against the backdrop of stupendous wealth in natural and mineral resources. Years of pillage by multinational corporations and unconscionable foreign and local business peoplehad combined to make the continent a restless forest of wars and banditry.

The Commission came to the conclusion that illicit financial flows from Africa originated from the following sources: commercial tax evasion, trade mis-invoicing, abusive transferpricing; criminal activities, including the drug trade, human trafficking, illegal arms dealing, smuggling of contraband; and bribery and theft by corrupt government officials[6]. The powerful nations of the west have devised different and complex means of ensuring that the growth of illicit financial flows from poor countries to rich western and Middle Easternnations continues.

Puppet Presidents whose loyalties are often to their former colonial masters are secured and kept in power against the wishes of their people. Thus, they use what the Commission refers to as Secret jurisdictions (cities, states or countries who maintain secrecy), Shell banks (they have office and addresses but no employees where they are located), Tax havens (which hide money for foreigners at zero or little taxes), Tradebased money laundering (where trade is used as a means of hiding illicit cash flows)[7].

In spite of the complicity of African leaders in the pauperization of its own people, finding answers to the continent’s many problems should be the subject of dialogue at various levels. In the course of this paper, I have tried to illustrate necessity of appreciating the historical, social, political and economic backdrop against which most African countries have become combustible units of endless circles of violence. It will be wrong for us to treat the issues of dialogue in isolation from the political economy of African countries. Although, the struggle to create an equal world has been going on over time, still, there are lessons to learn.

Mercifully, from history, we learn that the struggle for human dignity has been at the heart of human history. The world has fought two world wars and hundreds of other wars, nations have tried to quell internal rebellions. The emergence of the United Nations and the landmark United Nation’s Human Rights Declaration of 1948, coming barely three years after the end of the Second World War, laid the foundation for the quest for a peaceful world. Thesuper powers realized that if the world is to enjoy peace, dialogue and reconciliation between nations would have to be seen as fundamental tools for human development and progress. Thus, a commitment and a pledge to end war became inevitable. The United Nations has remained the gatekeeper for peace.

The Preamble of the Declarationon Human Rights statedthat:If man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, (that) human rights should be protected by the rule of law[8]. The first article of the Declaration further announced with a sense of urgency that: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood[9]. The Document went on to state that these rights inhere on us by virtue of our being part of the human family. They approximate the sentiments expressed in almost every sacred text and national Constitutions. The struggle for these rights has been at the heart of human history; without their realization there can be no peace and without peace, no development. Let us now see how the Catholic Church has responded to these challenges.

3: Catholic Church’s response to Violence, Peace building andDevelopment:

The Catholic Church has never been a mere observer in the theatre of the human struggle for justice, dignity and peace. This has been at the heart of her mission throughout human history. However, for the purpose of our reflections, we shall briefly look at the periods that coincide with Africa’s struggles for freedom. At this time, a white missionary leadership that could not be involved in the politics of the countries where they had evangelised predominantly dominated the Catholic Church. The Church had focused on providing Education, social welfare and health for our people. Similarly, African clerics were relatively absent from the high tables of decision making of the universal church. These meant that the leadership of the Catholic Church came late to the issues surrounding the struggle for liberation in Africa even after independence.

First, the convocation of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) marked a turning point in the Church’s engagement with modern times. This opening of the windows and a clearing of the cobwebs that had grown around a Church that had been rather closed to the world, gave the Church a greater vision of its role in the new world that was emerging. In the preface of the Document Gaudium et Spes, the Church announces its solidarity with the whole of human struggle by saying: The joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the people of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ. Indeed, nothing genuinely human fails to raise an echo in their hearts. This community realizes that it is truly linked with mankind and its history by the deepest of bonds.[10]

Second was the publication of the landmark Encyclical, Pacem in Terris (1963). The encyclical was a moral call to active engagement, seeking to raise the status of the human person and insist that development was only relevant to the extent that it placed the human person at the centre. Third was the publication of Nostra Aetate (1965) which signposted the Church’s appreciation of Islam as a religion and opened the doors for dialogue with people of other faiths.

Clearly, the Church was now well placed to offer the world a moral compass for navigating a new world order. Years and years later, despite the enormous work of the faith communities, our dreams of a just world order have remained an illusion. While the super powers have inoculated themselves against the violence of war and terrorism, they have turned the poorer nations of Africa into cesspools of violence in the continued exploitation of the resources required to fund their peace and development. The developing nations have become the theater for the Islamic induced terrorism that has now engulfed weak nations like Nigeria. These nations remain complicit in the massive movement of small and big arms that keep our peoples and countries permanently at war. This is the context in which dialogue is occurring in Africa. If we do not appreciate these complex issues, it will be impossible for us to answer the question, what is wrong with Africa or what is wrong with Christians and Muslims in Africa? Let me now try to look at these issues as they reflect the challenges that we face in Dialogue drawing lessons largely from Nigeria, knowing that other African countries face similar challenges.

The history of Nigeria has been intertwined with the history of Islam because the conquest of the old Sokoto caliphate(1804-1903) marked the highest point in the history of British colonialism. From then until date, the nation’s problems have revolved around the legacy of that fallen empire and the rest of the nation.

In working out the Constitutional processes leading to the nation’s independence, the colonial state totally ignored the fears and anxieties of the non-Muslim minority ethnic groups in the nation. For the purpose of our reflections, the northern situation is more pertinent. Then as now, most of the debate about religion has centred on the allegations of domination and religious discrimination by the Christian population in what is today central Northern Nigeria (made up of the states of Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue, Kaduna, Plateau, Nasarawa, Taraba).

In 1957 when the British government set up what was known as the Minorities Commission[11], the idea was to listen to the fears and anxieties of the minority ethnic groups in the run up to independence. When the British did nothing to allay these fears, the Christian community responded to Islamic domination after independence by setting up what they called, the Northern Christian Association. This platform would later assume a national dimension and become the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN.

The Muslims in the north had set up the Jama’atu Nasril Islam, JNI. Subsequent political development that saw the country go from regions to States necessitated the opening up of the platform to include other Muslims in the south west of Nigeria.

With the return of Democracy in 1999, a new platform, the Nigerian Interreligious Council, NIREC, emerged to more or less place both Christians and Muslims under one umbrella so as to enable leaders of both faiths speak with one voice to the government. Despite these platforms, there has been very little significant improvement in relations between Christians and Muslims. There are many reasons for this and I will cite only three.

First, the Muslims in northern Nigeria have not done much to show that they accept the supremacy of the Constitution and would like to live by that law. Thus, from 1978 until 1988, each time the nation has had to debate the status of its Constitution or propose amendments, the issues of the role and place of Islamic law have always marred the debates. By 1988, the military government barred the debate of Sharia law in further Constitutional debates. So, today, it can be argued that, between Boko Haram and the Shiite movement which is threatening the foundation of the corporate existence of Nigeria, beyond their recourse to violence there is no intrinsic difference between their claims and those of the Muslim bureaucratic, traditional and political elite who have continued to say they wish to see a country with Islam on the ascendancy!

The domination by the northern Nigeria Muslim elite has literally shut out the non-Muslim minorities from participating in power at the bureaucratic, political or economic levels. There are for example, no Christians in almost all the State assemblies of the States in the north even in places like Niger, Adamawa, Kaduna, Borno where their population is not insignificant. At the national level, the northern Muslims have produced a far more disproportionate percentage of Presidents than all the other parts of the country put together. Today the situation has worsened with the decision of the current government to hand over the leadership of all the nation’s Military and Security Agencies to Muslims! At this level, what should dialogue be about?

Second, there is the issue of the status of the interlocutors in our Dialogue and the expected outcomes. We have tended to present Christian religious leaders as being at the same level with Muslim traditional rulers. The reality is that Traditional rulers are the product of the state government and their powers are conferred by the state Governors. They receive salaries and can be removed by the government of the day. Many people mistakenly confer powers to the Sultan that he does not have when they refer to him as the leader of all Muslims in Nigeria. It is like saying that Cardinal Onaiyekan is the leader of all Christians in Nigeria! In the scenario we have painted above for example, what kind dialogue do to altar the course of things?

Thirdly, there is the assumption that Religion is the problem in Nigeria in particular and Africa in general. As we know, this position is popular but it is false. What we have is a case of inchoate, malfunctioning, decaying and thoroughly corrupt states in Africa whose maladministration has continued to create the conditions for the ascent of ethnic, regional and religious identities which continue to generate tensions. The absence of a sense of common citizenship, the none enforcement of the provisions of the Constitution as they pertain to human rights and welfare all contribute to create skepticism among our people.

For example, whenever violence erupts in Nigeria, government is quick to ask religious leaders to appeal for calm. However, these crises continue to escalate because, in reality, the issues are not about religion but about the inability of those who govern to address the issues and the grievances or seek to end impunity. When religious labels are slapped on these crises, they become impossible to resolve because the Police and the courts would often be charged with bias against one religion or the other as criminals are given religious tags!

4: Conclusion: what is the way forward?

Here, I will like to reflect on what the Catholic Church has done, is doing and should do with greater urgency. First, there is need for greater clarity and assertiveness by the Church on its core teachings on how to organise and manage society. Yes, we agree with and heed the warnings of successive Popes that the Church has no wish to replace the political leaders directly, but our teaching must find greater resonance in society.

We have already established the fact that it is the collusion of the governing elite with foreign interests and their proclivity toward outright theft and misuse of resources that has left Africa by the roadside of development.

Therefore, firstly, Catholics must dust up their Catechisms, become more educated on the Social teachings of the Church, and present with clarity and urgency the principles of governance such as the pursuit of the common good to the larger society.

The Catholic Bishops’ Conferences in Nigeria and Africa have created the necessary platforms such as the Commission on Mission, Departments of Mission and Dialogue, Justice, Peace and Development, Media and so on. The second challenge, therefore, is for these platforms to develop a greater sense of urgency and widen the communication of its message beyond the pews of its Churches. In these days of Social Media, the Catholic Church can and must do more with the opportunities that these vehicles of communication offer today.

To be sure, the global ambitions of Islam and its quest for domination in all strata of life remain key obstacles to dialogue. With no common commitment to common citizenship by both Muslims and Christians, our societies will remain polarized, thus creating the opportunity for the political class to manipulate and set our people against themselves on the grounds of religion, region, and ethnicity.

Thirdly, therefore, there isan urgent need for Pastoral agents such as Priests and Religious to develop more than a passing knowledge of the history of their countries. The root cause of most of our peoples relate to the very limited and very poor understanding of our national histories. Often, Priests listen to and believe the local rabble-rousers whose ignorance exploits local hate narratives. It is this lack of informed opinion by religious leaders about the historical contexts of conflicts that creates conditions for local tensions to metastasize. We must, with the universal Church continue to teach about the dignity of the human person and insist on concrete plans for the common good of all.

Fourthly, there is an urgent need for Africa to reset its historical template. There are so many distorted historical narratives and allegations against the other which continue to fuel hatred and instability. Yes, we must discuss what colonialism did to our people, what Muslims did to Christians, what Christians did to Muslims, what opportunities both Christians and Muslims have missed. There is now an urgent need for us to turn history into a weapon for unity, to understand the past, but work towards a clearer vision of a new society based on the crucible of truth.

Fifthly, against the backdrop of the persistence of the devaluation of human life through the re-writing of our human values, there is the need for the Catholic Church to continue in her pursuit of the principles of Mater et Magistra, Mother and Teacher. In spite of, or even because of the crises of the last few years, the Church must renew its commitment to a just moral order based on God’s revealed truth. Its prophetic voice must continue to resound, welcome or unwelcome. We must continue to shine a greater light and offer a clearer moral compass for the world to seek greater solidarity so we can win the war against crippling inequalities that have become an excuse for terrorism today. The corrosive effect of capitalism must be confronted with the truth of the teaching of the Church on the Common destination of human goods and the urgent need for human dignity.

In recent times, successive Popes, especially St. John Paul 11, in various Encyclicals and Synods, charted the path for a new cause in the world. Nowhere was this urgency better expressed than in Communist Europe, Africa and Asia. Papal visits, endless sermons, apostolic exhortations, increased visibility for Africa and Asia in the universal Church through expansion of the ecclesiastical jurisdictions and elevation of Africans to key positions, all created a huge momentum for the Catholic Church to change the course of our societies. The context and contents of these developments are already well known to this audience to merit direct or selected references. Sadly, a good part of that momentum has been lost. This is why this Conference is so important.

In keeping with tradition, Popes Benedict, Emeritus, and Francis have continued with the challenge of offering the world a new template for peace. When Pope Benedict issued two Encyclicals, Deus Caritas Est (2005), Caritas in Veritate (2009) he raised the bar in helping the world navigate the turbulent waters of capitalist excesses. These documents had raised the issues that would come to a head in 2008 when the world markets collapsed under the weight of Capitalist exploitation and arrogance! The call of Pope Francis for Christians to,Wake up the world[12] must therefore be taken with greater urgency before another cataclysm sets upon us. With hindsight, the canonization of Archbishop Romero could not have come at a better time. By taking this decision, the Church has pointed out the need for the Church to return to the trenches and seek to renew the face of the earth with greater urgency. May committed, selfless, courageous and prophetic witness of St. Romeo provide a model for Christian leaders today.

For Africa, Dialogue will have to mean more than mere talking by religious leaders who have no powers to enforce to laws of the states. Their moral voices will continue to call attention to the iniquities of our countries and communities, but the task of building viable nations and communities will have to be undertaken by the state through those who hold public office. To this end, the Church must educate and encourage its people to become more actively involved in shaping the lives of their nations. It is the only way to reverse the cultural, social, political and even economic violence that encourages exclusion and dehumanizes our entire people across different identities.

[1] Rudyard Kipling: The White Man’s Burden. This poem was written by the author(1899-1920) in the wake of the American war with the Philippines. It has since been presented as the justification for colonialism in many quarters

[2] Between 1884-5, the emerging European superpowers had assembled to address the need to avoid open conflict of their interests in Africa. It was at this Conference that they took the decisions to parcel out what would become the continent of Africa.

[3] Basil Davidson: The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation State

(London. 1993)

[4] Michael Peel’s award winning book, A Swamp Full of Dollars, tells of the story of the tragic impact of Oil on the Nigerian economy and the irony of poverty in the Niger Delta.

[5] Illicit Financial Flows: Report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa (Commissioned by the AU/ECA Conference of Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, 2017)

[6] Illicit Financial Flows, p P9

[7]Illicit Financial Flows, p10

[8] Universal Declaration on Human Rights was proclaimed on 10th December 1948

[9] Universal Declaration on Human Rights, art. 1

[10]Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World, (December 7th, 1965), Preface.

[11]Report of the Commission to Enquire into the Fears of Minorities and the Means of Allaying Them.

(July, 1958). The Commission became necessary and was set up because of the pre-independence agitations across the country by the Minority ethnic groups which felt dominated and oppressed by the three dominant ethnic blocks of Hausa-Fulani(North), Igbos(South East) and Yoruba(South West). To divide and weaken the south and uphold the domination of the north, the Mid west state was created out of the South West!

[12] Apostolic Letter to All Consecrated People on the Occasion of the Year for Consecrated Life

Vatican City, 24/11/14